This month, we sat down with Fatimah Loren Dreier, Executive Director of the Health Alliance for Violence Intervention (HAVI), an organization that fosters hospital and community collaborations to advance equitable care. Fatimah has dedicated her career to addressing the epidemic of violence in America, today we’re sitting down to talk about violence through a public health lens, her work advising the White House on this crisis, and how to think about and tackle big problems.

Listen to the interview or check out some highlights below:

What is The Health Alliance for Violence Intervention?

I lead an organization that helps stand up a model of care called hospital-based violence intervention. And it's a model of care, devised over decades, that was championed by trauma surgeons, former patients who were gunshot wound victims. People who were seeing on the ground that violence in America, gun violence in America, is cyclical.

So they were seeing that people who've been violently injured, they're treated for their physical wounds and then they are discharged and go right back out into environments that have not fundamentally changed and as a result, unfortunately are re-injured. Their risk of re-injury is something like 30 to 40% and so they return to the hospital either injured again, or unfortunately, sometimes fatally wounded. And this trend has existed in the country for quite some time, without any major push to address these issues, to better research them, to provide a suite of interventions that can make a difference in the lives of those who are violently injured.

It's really about addressing some of the fundamentals of healthcare. Unfortunately, this has been an issue that's been woefully neglected. So what I do is I've really helped take a model that was providing support to violently injured patients, a behavioral model that addresses some of those root causes of violence - and was found in some randomized control trials to help actually mitigate the impact of violence - take that model and help scale it in the United States and increasingly internationally.

On hospital-based-violence-intervention programs (HVIPs):

At its very early stage, the foundation of our model is really bringing people to the hospital who understand, who have some lived experience, to share peer-to-peer. We find this throughout health and behavioral health, that hearing from credible people who have experience with the particular issue that you face is an incredibly effective way of transmitting messages.

That idea has scaled in this country and it has led to incredible studies that demonstrate the effectiveness of those messages and addressing mental health challenges. We see shifts in behavioral outcomes such as substance use, alcohol use, anger issues, that people who are hearing these messages now, engaged in this sort of support, we see decreases in their risk and it's incredibly powerful.

It's not just about saying this is a mental health issue and I'm not saying they're doing clinical care, right? There's still a role for psychologists and social workers. But alongside that, having a credible messenger to relay some of those message, an enormously powerful tool in transformation.

Making the moral and business case for addressing violence as a public health issue:

As you can imagine, the healthcare system and hospitals have a significant task. They're tasked with addressing a plethora of health issues and needs of patients. And as I said, this has unfortunately been an issue that's been woefully neglected. So when we approach a hospital and we recommend that they start a program, we often need clinical champions first.

We need the trauma surgeons, the emergency physicians who are seeing the patients, we really need their buy-in first because they're the ones that are going to be able to share stories about what they see in the trauma bay and share that this is an idea that they've seen at other hospitals. They've talked to their colleagues in other places that are implementing this. We find that peer-to-peer relationship is also really important. And to share the value of providing these services to patients that it's just the right thing to do. That's the moral case.

Some of the barriers there, when you're making a moral argument for providing health services, the challenge we find is that people often think of violence as purely a criminal justice issue. So to provide a reframe that it's a public health issue and that health systems need to be engaged. That's a significant paradigm shift and so, in the early days, you certainly saw a lot of resistance or confusion, curiosity, but certainly there was a real prevailing lack of knowledge about why violence would be a public health issue. That's changed over time. Just like any innovation, it takes time for and early adopters to really spread the word. There is also a business case for this.

Violence is expensive. By some estimates it costs the United States $280 billion annually. For those who are violently injured, some of our cost analysis per patient, we're looking at 30 or $40,000 in terms of treatment, some of it's reimbursed, some of it's not. Most of it's not. So there's a real, concern around the cost of violence. And for us, there's been a real march towards how to build a business case for violence intervention strategies. We've worked for many years and I'm really proud to say we've really succeeded in building a business case. We've secured billions of dollars for this work in the United States.

On her work advising the White House on gun violence:

I advise and support the Biden administration, not only supporting the President and the domestic policy council in communicating to the country the value of this work, but also the reimbursement structures that are required to sustain this work in hospitals. We are currently working, state by state, Connecticut and Illinois being one of the first states to offer a reimbursed benefit related to violence prevention services. And now we're in six states and it's expanding rapidly.

There's some real opportunities for that reimbursement mechanism that makes it sustainable, that makes it a business line, just like every other line. When heart attacks happen, there's a business line. You can reimburse for it. You can pay people for their work. So we really care about both. We want to make those arguments strong.

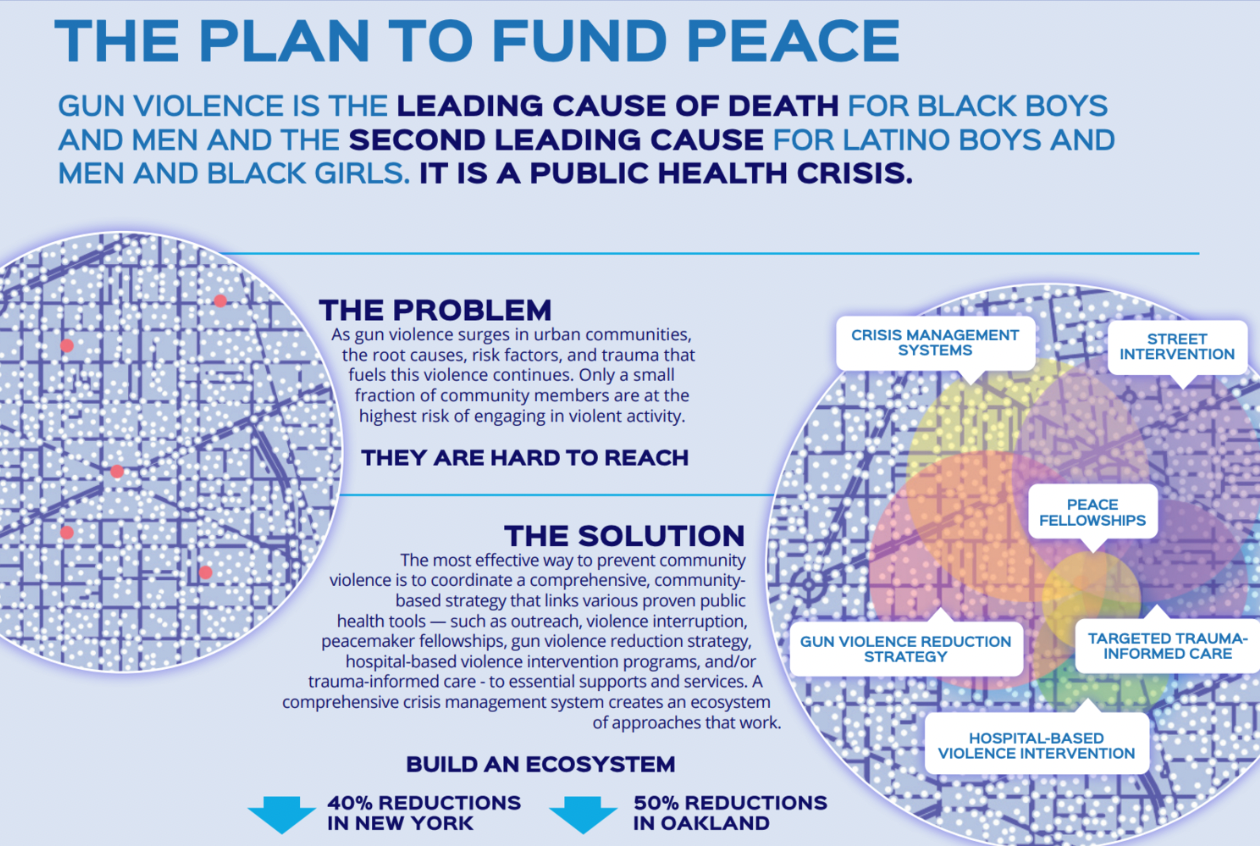

There's also, this larger prevailing conversation about racial equity in our country and health equity and recognizing that it's important to acknowledge that this has been neglected. Violence is the leading cause of death for black boys and men. It's the second leading cause of death for Latinos. And that's been the case for quite some time. This is not new.

It's an epidemic that has been narrowly impacting communities of color. It's no coincidence that it also has been in a particular set of issues that haven't received the kind of focused attention and innovation that other health issues have. And this is something we wanna say explicitly that racial equity is important here. Health equity is really important and that if we address these well, we transform communities, not just the patients, but we were looking structurally about how we can make changes in communities.

So that's really exciting. So we talk about all those things. We're not just convincing the hospital administrator. We want to impart the value of this to the mayor, to the governor, to senators, to the President. And we work at every level to ensure that this is a value that we have in society.

How do we shift the general public's understanding of this issue from talking points to understanding the problems and their root causes.

It's the million dollar question. I do think that we have examples in history of shifting our perspective about something in such a way that new ideas and opportunities become available to pull from those examples. You leverage them and you articulate a new path forward.

On the health side, things like the transformation of tobacco use in this country. If you remember in the forties or fifties, you'd see cigarettes everywhere. People are smoking in hospitals and airplanes and that's shifted significantly and it's taken a slate of both research and new ways in healthcare, I think to address cessation and marketing and ads, it takes a whole host of things in order to make this possible, but you first have to understand current sentiment and I think it is something we don't fully understand.

We just released a national poll that explored some of the sentiment in partnership with Data for Progress, and we were actually very surprised to learn a number of things. We asked, for example, what are peoples' prevailing views about gun violence? And we found 50% of African American and Latino communities were concerned about violence in their own community. That's a significant number. And for White Americans, one out of every three are concerned about violence in their own community.

This is something that a significant portion of the population is thinking about. We found that 46% of the sample polled believe that addressing root causes of violence, so trauma and poverty, were going to be fundamental to changing gun violence in the country. It's about addressing things like mental health. That's a great place to start. That demonstrates that some of the work we've done making that case is actually resonating with voters.

Then we have upwards of 60% of likely voters who say that they actually support funding this work, that they want to see more resources, they want to see Congress act. I think that is very powerful. That these are not foreign ideas or so novel only a small part of the electorate knows about that. We've not only made the case, but we are making it over and over again and more and more people understand what it means to provide health approaches and are beginning to support those. And that's how change happens. You begin to see it out in society that demand increases and then change happens. So it's really exciting. I think there's far more to do, but it's a great start.

When you are thinking about big problems, big seismic shifts in thinking, how do you even begin to figure out what you need to do day-to-day?

There is an enormity and it's very easy to get stuck in how big this is; how big the problem is, how big the opportunity is. At some point, one needs to translate big ideas into digestible, practical, operationally and strategically sound action steps. I happen to really love doing that and it's a strength of mine. But I will admit, there are days where I can really feel the kind of enormity of the task at hand.

My secret is to get out of the office, go for a walk, take some time away from it and open my lens a little bit. Somewhere in the recesses of my mind, that operational brain just begins to order things. There is really no problem in the world that doesn't have a first step. And I think that sometimes it can feel too small, but I find the muscle of taking the first step creates the opportunity to take the next step.

Sometimes, people think they need to know all the steps before they start. I've never found that to be true. I'm not saying take a walk without looking both ways before you cross the street, but it's often the case, especially with these large problems, that you'll need to take a few steps first and then reassess. What you discover there is going to be different than what you knew a few steps ago. And you're gonna have to just step out on faith or into that uncertainty and be willing to tolerate that uncertainty.

People are really comforted by big, thoughtful plans that become obsolete, the minute you begin implementation. What I'd rather have is set of assumptions that I constantly check in on and then a really refined set of tasks that will get you enough along the way that you can then reassess your assumptions and reassess the landscape.

To learn more about their HAVI, visit their at our website www.thehavi.org or follow HAVI on Twitter @theHAVI.

Read about the $5B Plan to Fund Peace.